See the main page of Tour de Sol 2007 Photos at http://www.AutoAuditorium.com/TdS_Reports_2007/photos.html

At the awards ceremony for the 21st Century Automotive Challenge we heard Nancy Hazard review the American Tour de Sol from its incarnation to its present hiatus.

Here are the slides along with the text of that presentation, provided by Nancy.

Hello, I am Nancy Hazard of World Sustain. I was involved

with the Northeast Sustainable Energy Association's (NESEA) Tour de Sol from

its start in 1989. That first year I was a volunteer. I later became the

director, and worked on it for 18 years. Ollie Perry, Director of the new 21st

Century Automotive Challenge has graciously asked me to talk about my

perspective of the highlights of the Tour de Sol, and suggestions of what I

think needs to be done to continue to move forward the issues promoted by the

Tour de Sol.

Hello, I am Nancy Hazard of World Sustain. I was involved

with the Northeast Sustainable Energy Association's (NESEA) Tour de Sol from

its start in 1989. That first year I was a volunteer. I later became the

director, and worked on it for 18 years. Ollie Perry, Director of the new 21st

Century Automotive Challenge has graciously asked me to talk about my

perspective of the highlights of the Tour de Sol, and suggestions of what I

think needs to be done to continue to move forward the issues promoted by the

Tour de Sol.

In 1987 Urs Munwyler stared the Tour de Sol competition in Switzerland. In

1988, Rob Wills, PhD candidate at Dartmouth College traveled to that event with

the Dartmouth solar car team. Upon returning, folks at MIT and Dartmouth got

to talking about how it would be great to have an event like the Tour de Sol in

the USA. Rob sat on the NESEA board, and so he proposed that they take it on.

NESEA was interested, and they received permission from Urs to create the

American Tour de Sol. This photo shows Dr. Robert Wills starting the Dartmouth

car in the first Tour de Sol that started in Montpelier, May 1989.

The purpose

of the event was to showcase what Photovoltaics (PV) can do. Although I knew

that PV created electricity from sunlight, I can still remember this moment.

I found it tremendously moving and exciting to see a car go down the road using

energy created from the sun that I was instantly hooked!

In 1987 Urs Munwyler stared the Tour de Sol competition in Switzerland. In

1988, Rob Wills, PhD candidate at Dartmouth College traveled to that event with

the Dartmouth solar car team. Upon returning, folks at MIT and Dartmouth got

to talking about how it would be great to have an event like the Tour de Sol in

the USA. Rob sat on the NESEA board, and so he proposed that they take it on.

NESEA was interested, and they received permission from Urs to create the

American Tour de Sol. This photo shows Dr. Robert Wills starting the Dartmouth

car in the first Tour de Sol that started in Montpelier, May 1989.

The purpose

of the event was to showcase what Photovoltaics (PV) can do. Although I knew

that PV created electricity from sunlight, I can still remember this moment.

I found it tremendously moving and exciting to see a car go down the road using

energy created from the sun that I was instantly hooked!

At the time, I had been building ''solar homes'' because I was deeply troubled

by the fact that our world had been built on oil -- a finite resource. These

graphs show the production of oil from specific wells -- from discovery, to

developing the equipment to pump the oil. In each case we can see the growth

of productivity of the well, the peak, and then the falling of productivity.

This is typical of all oil wells. It is called Hubert's curve, and when we

aggregate all the oil wells of the world we can expect the same curve -- and in

fact we are seeing this pattern today. Most people agree that the world oil

production is at the peak, commonly referred to peak oil. But the demand for

oil is growing dramatically! So the need to change the world is more urgent

than ever At that time, I wanted to work on getting the world off of oil, and

when I learned that transportation uses 2/3rds of all the oil used in the US, I

immediately decided to switch from building to the Tour de Sol.

At the time, I had been building ''solar homes'' because I was deeply troubled

by the fact that our world had been built on oil -- a finite resource. These

graphs show the production of oil from specific wells -- from discovery, to

developing the equipment to pump the oil. In each case we can see the growth

of productivity of the well, the peak, and then the falling of productivity.

This is typical of all oil wells. It is called Hubert's curve, and when we

aggregate all the oil wells of the world we can expect the same curve -- and in

fact we are seeing this pattern today. Most people agree that the world oil

production is at the peak, commonly referred to peak oil. But the demand for

oil is growing dramatically! So the need to change the world is more urgent

than ever At that time, I wanted to work on getting the world off of oil, and

when I learned that transportation uses 2/3rds of all the oil used in the US, I

immediately decided to switch from building to the Tour de Sol.

Rob Wills was fond of saying that all he wanted to do was ''change the

world''.

When the Clean Air Act was passed in 1990, California began talking about

creating a program that would require the auto makers to build and sell a

certain number of electric vehicles in California if they wanted to keep

selling conventional vehicles in that state. And so the mission of the Tour de

Sol changed. We felt that to change the world, we needed to offer practical

vehicles that people could use on a daily basis -- and our vision was electric

vehicles (EVs) charged by renewably produced electricity! In my mind it seemed

a lot easier to reduce oil use in transportation than from buildings because a

car is an ''appliance'' that most people replace every 10 years. All we needed

to do is to get the autos to make a more efficient appliance, an electric

appliance, and for people to buy them. As it turned out this would be much

more difficult than I ever imagined!

Rob Wills was fond of saying that all he wanted to do was ''change the

world''.

When the Clean Air Act was passed in 1990, California began talking about

creating a program that would require the auto makers to build and sell a

certain number of electric vehicles in California if they wanted to keep

selling conventional vehicles in that state. And so the mission of the Tour de

Sol changed. We felt that to change the world, we needed to offer practical

vehicles that people could use on a daily basis -- and our vision was electric

vehicles (EVs) charged by renewably produced electricity! In my mind it seemed

a lot easier to reduce oil use in transportation than from buildings because a

car is an ''appliance'' that most people replace every 10 years. All we needed

to do is to get the autos to make a more efficient appliance, an electric

appliance, and for people to buy them. As it turned out this would be much

more difficult than I ever imagined!

We formed an advisory group of participants and others and we talked about how

we were going to ''change the world'' with the Tour de Sol. We decided we

needed to demonstrate what was possible. Therefore we needed to inspire

everyone to get involved in building the vehicle of our dreams -- students,

auto manufacturers, engineers, hobbyists We needed funds to support our effort

-- and we wanted the auto companies, our government and electric utilities to

get involved -- so we invited them to enter the competition and become sponsors

-- and many of them did! And we wanted to educate politicians and the general

public, so we mounted major media campaigns around each annual event -- calling

for participants, and then promoting the event itself, its entrants, sponsors,

and its successes.

We formed an advisory group of participants and others and we talked about how

we were going to ''change the world'' with the Tour de Sol. We decided we

needed to demonstrate what was possible. Therefore we needed to inspire

everyone to get involved in building the vehicle of our dreams -- students,

auto manufacturers, engineers, hobbyists We needed funds to support our effort

-- and we wanted the auto companies, our government and electric utilities to

get involved -- so we invited them to enter the competition and become sponsors

-- and many of them did! And we wanted to educate politicians and the general

public, so we mounted major media campaigns around each annual event -- calling

for participants, and then promoting the event itself, its entrants, sponsors,

and its successes.

Creating the scoring system was our tool to get the vehicles built that we

wanted to demonstrate. We started with the Swiss Tour de Sol Rules book, which

was very detailed about safety issues, but was not oriented to practical

vehicles, so with a committee lead by Rob Wills, who had become the Technical

Director of the Tour de Sol, each year we revised the Rules Book, as well as

the scoring system. Technical testing and safety were important components of

the event from the start. The Swiss event focused on reliability and range.

Power could only come from electricity produced by PV on the vehicle, or on a

separate PV charging station brought to the event. As we moved to practical

vehicles, the cars charged from the grid, and driving range became a major push

of the event. While many felt that 50 miles was adequate, auto companies and

most consumers were not convinced. Efficiency was added to the scoring system

at some point. The electric utility companies were interested in understanding

how EVs might affect the electric grid, and so we were able to recruit Bob

Goodrich, head of Northeast Utilities R&D, to build us a charging trailer

(really a distribution system -- a trailer with lots of receptacles and

instrumentation on the receptacles.).

The charging trailer got its electricity

from a ''convenient'' transformer on an electric utility pole -- a rather

expensive connection, but worth it to the utility companies.(Later we resorted

to a biodiesel-powered generator.) We revised the trailer many times and

finally moved the data collection system from the trailer to individual house

meters that entrants were responsible for hooking into their recharging

systems. Efficiency led to very light vehicles, and so we added the autocross

event to ensure that the vehicles were robust enough to withstand daily

practical use and be safe. Around 2000 we added climate change emissions to

the scoring system. We worked with US DOE's Argonne National Laboratory so

that we could quantify the climate change emissions from various fuels. While

this all made the scoring system tremendously complicated, and Rob and others

struggled with the mechanics of spreadsheets and databases and producing

accurate scoring results in a short time span, we felt strongly that we had to

judge the vehicles in this way. Nobody else was doing this work! For several

years we ran gasoline vehicles in the event so that we would have data that

could compare conventional vehicles to these new vehicles. The data we

collected was used by many non-profits. By this time we had all kinds of

vehicles in the competition -- but I'm getting way ahead of myself!

Creating the scoring system was our tool to get the vehicles built that we

wanted to demonstrate. We started with the Swiss Tour de Sol Rules book, which

was very detailed about safety issues, but was not oriented to practical

vehicles, so with a committee lead by Rob Wills, who had become the Technical

Director of the Tour de Sol, each year we revised the Rules Book, as well as

the scoring system. Technical testing and safety were important components of

the event from the start. The Swiss event focused on reliability and range.

Power could only come from electricity produced by PV on the vehicle, or on a

separate PV charging station brought to the event. As we moved to practical

vehicles, the cars charged from the grid, and driving range became a major push

of the event. While many felt that 50 miles was adequate, auto companies and

most consumers were not convinced. Efficiency was added to the scoring system

at some point. The electric utility companies were interested in understanding

how EVs might affect the electric grid, and so we were able to recruit Bob

Goodrich, head of Northeast Utilities R&D, to build us a charging trailer

(really a distribution system -- a trailer with lots of receptacles and

instrumentation on the receptacles.).

The charging trailer got its electricity

from a ''convenient'' transformer on an electric utility pole -- a rather

expensive connection, but worth it to the utility companies.(Later we resorted

to a biodiesel-powered generator.) We revised the trailer many times and

finally moved the data collection system from the trailer to individual house

meters that entrants were responsible for hooking into their recharging

systems. Efficiency led to very light vehicles, and so we added the autocross

event to ensure that the vehicles were robust enough to withstand daily

practical use and be safe. Around 2000 we added climate change emissions to

the scoring system. We worked with US DOE's Argonne National Laboratory so

that we could quantify the climate change emissions from various fuels. While

this all made the scoring system tremendously complicated, and Rob and others

struggled with the mechanics of spreadsheets and databases and producing

accurate scoring results in a short time span, we felt strongly that we had to

judge the vehicles in this way. Nobody else was doing this work! For several

years we ran gasoline vehicles in the event so that we would have data that

could compare conventional vehicles to these new vehicles. The data we

collected was used by many non-profits. By this time we had all kinds of

vehicles in the competition -- but I'm getting way ahead of myself!

While the event grew from 6 entrants in 1989 to over 50 entrants, I'm going to

tell the story of the entrants with just a few examples. Solectria Corporation

was the early hero of the Tour de Sol. James Worden, who was often referred to

as the ''Henry Ford of EVs,'' and Anita Rajan, MIT student soon to be wife of

James and President of Solectria, founded Solectria Corporation in 1980 with

other MIT students. The first vehicle MIT entered is on the left with James in

white. This is the solar vehicle that went to the Swiss Tour de Sol and the

first few American Tour de Sols. The vehicle on the right James fondly refers

to as his ''tin box.'' James built this electric car as a high school project,

and he used it to commute from his home in Arlington to MIT while he was in

college. This was the first purpose-built EV that I had seen! James' sister

is standing next to the car.

While the event grew from 6 entrants in 1989 to over 50 entrants, I'm going to

tell the story of the entrants with just a few examples. Solectria Corporation

was the early hero of the Tour de Sol. James Worden, who was often referred to

as the ''Henry Ford of EVs,'' and Anita Rajan, MIT student soon to be wife of

James and President of Solectria, founded Solectria Corporation in 1980 with

other MIT students. The first vehicle MIT entered is on the left with James in

white. This is the solar vehicle that went to the Swiss Tour de Sol and the

first few American Tour de Sols. The vehicle on the right James fondly refers

to as his ''tin box.'' James built this electric car as a high school project,

and he used it to commute from his home in Arlington to MIT while he was in

college. This was the first purpose-built EV that I had seen! James' sister

is standing next to the car.

Solectria's first purpose-built EV was the Lightspeed -- in the center. It is

flanked by its bread and butter product -- Geo Metros converted to electric

propulsion. Anita is in the front row far left, James is between the yellow

and red cars, Andy Haefitz is to his right, and Gill Pratt is on the far right.

Solectria's first purpose-built EV was the Lightspeed -- in the center. It is

flanked by its bread and butter product -- Geo Metros converted to electric

propulsion. Anita is in the front row far left, James is between the yellow

and red cars, Andy Haefitz is to his right, and Gill Pratt is on the far right.

Solectria's entries were always an incredible draw for the media. Each year

their entries would break their previous records. Range records of 50 grew to

100, 150, 200, and then 250 miles on a single charge! Solectria paid

incredible attention to efficiency. Their GeoMetro's routinely drove one mile

on 150 Watt-hours or less.

At 10 cents a kilowatt hour, that translates to 0.7 cents

per mile for fuel! In the heyday of the Tour de Sol news of the Tour de Sol

was carried on network news, over 300 news article were printed, and it was

estimated that there were over 100 million media impressions!

Solectria's entries were always an incredible draw for the media. Each year

their entries would break their previous records. Range records of 50 grew to

100, 150, 200, and then 250 miles on a single charge! Solectria paid

incredible attention to efficiency. Their GeoMetro's routinely drove one mile

on 150 Watt-hours or less.

At 10 cents a kilowatt hour, that translates to 0.7 cents

per mile for fuel! In the heyday of the Tour de Sol news of the Tour de Sol

was carried on network news, over 300 news article were printed, and it was

estimated that there were over 100 million media impressions!

We also started a conference -- the first and only solar and EV conference in

the country for many years. NESEA held many conferences for builders and

architects at the time, so this seemed like a logical step. At first we saw

the conference as a way to get more Tour de Sol entrants -- by offering past

and future entrants an opportunity to share information and enthusiasm. The

Symposium grew into the largest EV conference in the country with a trade show

with auto and bus manufacturers, component manufacturers, and start-up

companies such as Solectria and Solar Car Corp. The last conference NESEA held

was in New York City. It drew over 600 attendees. Then the EVAA (Electric

Vehicle Association of the Americas), know today as the EDTA (Electric Drive

Transportation Association), started holding an electric vehicle conference --

and it continues to hold an annual conference on electric-drive vehicles. The

EDTA is the trade organization and lobbying arm of those interested in

electric-drive vehicles including auto makers, battery manufacturers, electric

utility company, hydrogen fuel cell advocates and others.

We also started a conference -- the first and only solar and EV conference in

the country for many years. NESEA held many conferences for builders and

architects at the time, so this seemed like a logical step. At first we saw

the conference as a way to get more Tour de Sol entrants -- by offering past

and future entrants an opportunity to share information and enthusiasm. The

Symposium grew into the largest EV conference in the country with a trade show

with auto and bus manufacturers, component manufacturers, and start-up

companies such as Solectria and Solar Car Corp. The last conference NESEA held

was in New York City. It drew over 600 attendees. Then the EVAA (Electric

Vehicle Association of the Americas), know today as the EDTA (Electric Drive

Transportation Association), started holding an electric vehicle conference --

and it continues to hold an annual conference on electric-drive vehicles. The

EDTA is the trade organization and lobbying arm of those interested in

electric-drive vehicles including auto makers, battery manufacturers, electric

utility company, hydrogen fuel cell advocates and others.

Bob Stempel put the NESEA conference on the map by accepting our invitation to

keynote our conference in 1992 when he was chair of General Motors. At that

conference he met James Worden, and they formed a relationship that enabled

Solectria to receive Geo Metro gliders (body with no motor). In 1993 Bob

Stempel moved to Energy Conversion Devices, and worked with Stan Ovshinksy to

create the Ovonic nickel metal hydride battery company. In this photo, Bob

(back left) joins Solectria Corporation at the 1996 Tour de Sol finish line to

celebrate the success of the Solectria Sunrise, which drove 373 miles on a

single charge using the Ovonic battery system! This was an amazing

achievement!

Bob Stempel put the NESEA conference on the map by accepting our invitation to

keynote our conference in 1992 when he was chair of General Motors. At that

conference he met James Worden, and they formed a relationship that enabled

Solectria to receive Geo Metro gliders (body with no motor). In 1993 Bob

Stempel moved to Energy Conversion Devices, and worked with Stan Ovshinksy to

create the Ovonic nickel metal hydride battery company. In this photo, Bob

(back left) joins Solectria Corporation at the 1996 Tour de Sol finish line to

celebrate the success of the Solectria Sunrise, which drove 373 miles on a

single charge using the Ovonic battery system! This was an amazing

achievement!

Much to NESEA's amazement and surprise, high schools began to build EVs and

enter them in the Tour de Sol! Peterboro High School in New Hampshire was the

first high school to enter the Tour de Sol in about 1991.

This group went on to

create several other beautiful EVs, and other high schools took on the

challenge, and brought amazing entries such as Topher Waring's VW bus efforts,

Earl Billings one-person solar commuter, and Paul O'Brien's fuel cell trike to

name a few. By 2006, the Tour de Sol had more entries from high schools than

any other single source.

Much to NESEA's amazement and surprise, high schools began to build EVs and

enter them in the Tour de Sol! Peterboro High School in New Hampshire was the

first high school to enter the Tour de Sol in about 1991.

This group went on to

create several other beautiful EVs, and other high schools took on the

challenge, and brought amazing entries such as Topher Waring's VW bus efforts,

Earl Billings one-person solar commuter, and Paul O'Brien's fuel cell trike to

name a few. By 2006, the Tour de Sol had more entries from high schools than

any other single source.

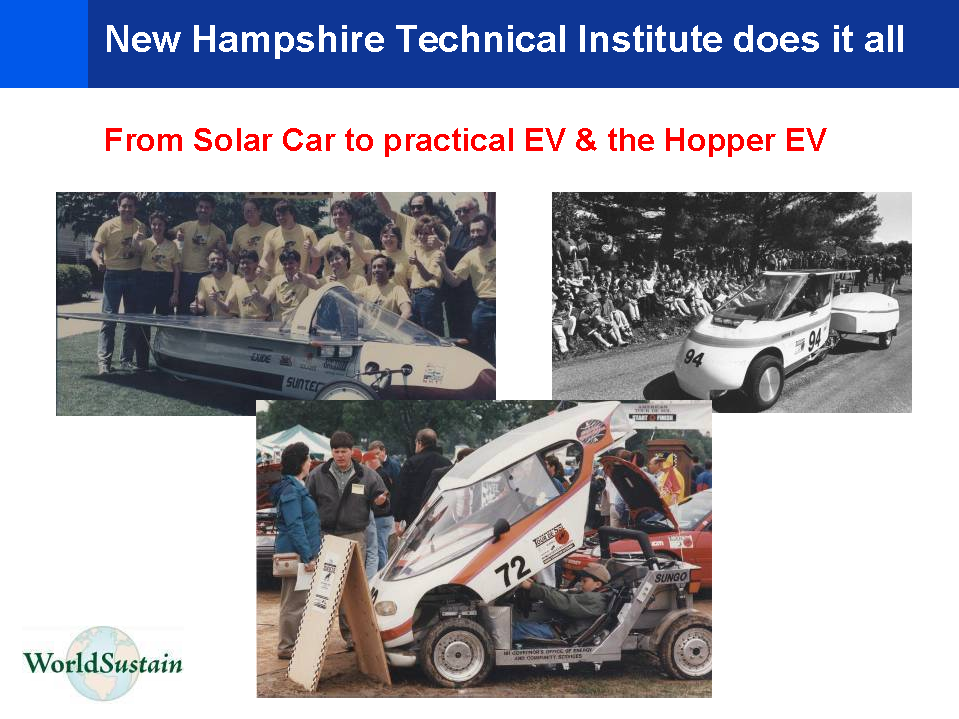

New Hampshire Technical Institute participated for over 10 years, and the

evolution of their entries reflects the growth of the Tour de Sol. They

started with a solar racing car (top left). They then built the Sungo, a

practical 2-seater commuter vehicle, with PV on the roof. This vehicle was

very efficient. At first it used lead acid batteries, and then the students

began experimenting with the Ovonic nickel metal hydride batteries. The top

right photo is a vehicle that Tom Hopper, the team advisor and professor

created. He used this beautiful one-person EV to commute from his off-grid

home to work every day. After several years he built the trailer so he could

go anywhere -- the trailer had an auxiliary power unit (APU) i.e. a gasoline

engine. In one amazing NYC to DC event, instead of trailering the vehicle to

the event to participate, he drove to and from the event! This was a major

demonstration of the practicality of the vehicles we were showcasing!

New Hampshire Technical Institute participated for over 10 years, and the

evolution of their entries reflects the growth of the Tour de Sol. They

started with a solar racing car (top left). They then built the Sungo, a

practical 2-seater commuter vehicle, with PV on the roof. This vehicle was

very efficient. At first it used lead acid batteries, and then the students

began experimenting with the Ovonic nickel metal hydride batteries. The top

right photo is a vehicle that Tom Hopper, the team advisor and professor

created. He used this beautiful one-person EV to commute from his off-grid

home to work every day. After several years he built the trailer so he could

go anywhere -- the trailer had an auxiliary power unit (APU) i.e. a gasoline

engine. In one amazing NYC to DC event, instead of trailering the vehicle to

the event to participate, he drove to and from the event! This was a major

demonstration of the practicality of the vehicles we were showcasing!

Electric utility companies had been bringing prototype EVs built by the major

auto makers (OEMs) to the Tour de Sol for several years, but when Ford brought

its Ecostar to the Tour de Sol in 1994 it was a watershed year for me. This

was the first serious OEM entry. Roberta Nichols, Ford executive and a race car

driver drove the route two weeks before the event with her navigator. Ford

mounted a major media campaign about their entry, and Roberta was doing radio

interviews around the country whenever she was not driving. Needless to say

they took first place in the Production Category! The Ecostar was a beautiful

EV with over 100 miles driving range using sodium sulfur batteries. These

batteries were popular in Europe, and Ford Motor Company had invested heavily

in them. In the next year or so, Ford was to experience two fires with this

battery technology, and their EV program started loosing its forward momentum

as they struggled to find suitable replacement batteries. The starting

ceremony at the World Financial Center in New York City was amazing with over

50 entrants, and many exhibitors including an electric tank from the US

Department of Defense.

Electric utility companies had been bringing prototype EVs built by the major

auto makers (OEMs) to the Tour de Sol for several years, but when Ford brought

its Ecostar to the Tour de Sol in 1994 it was a watershed year for me. This

was the first serious OEM entry. Roberta Nichols, Ford executive and a race car

driver drove the route two weeks before the event with her navigator. Ford

mounted a major media campaign about their entry, and Roberta was doing radio

interviews around the country whenever she was not driving. Needless to say

they took first place in the Production Category! The Ecostar was a beautiful

EV with over 100 miles driving range using sodium sulfur batteries. These

batteries were popular in Europe, and Ford Motor Company had invested heavily

in them. In the next year or so, Ford was to experience two fires with this

battery technology, and their EV program started loosing its forward momentum

as they struggled to find suitable replacement batteries. The starting

ceremony at the World Financial Center in New York City was amazing with over

50 entrants, and many exhibitors including an electric tank from the US

Department of Defense.

In 1998 Toyota approached us and asked if we'd be interested in having their

Toyota Prius -- a new hybrid vehicle that had not yet been introduced into the

USA -- as our Pace car. To be honest, this offer presented a dilemma for

NESEA.

A gasoline vehicle, even an efficient gasoline vehicle, did not

demonstrate our dream of an EV charged by renewables. In fact, for several

years, we had allowed student hybrid vehicles (HEV) to enter, because the US

Department of Energy (DOE), which was a major sponsor of the Tour de Sol, also

sponsored a collegiate-level HEV competition, and they wanted to offer those

teams more opportunities to compete in events. We had reluctantly agreed,

since they held the purse strings, and again we reluctantly agreed to Toyota's

proposal for the same reason Pictured here is US DOE Secretary Pena waving the

checkered flag as the Toyota Prius arrived in DC. To be honest, this was also

an uncomfortable event for the DOE, because they did not want to recognize the

Prius because it was not ''made in the USA.'' In 1999 Honda became a major

sponsor of the Tour de Sol and shared the title sponsorship with the DOE for

the following three years. In 1999 Honda started showcasing the Honda Insight,

the first hybrid vehicle on the US market, and shortly thereafter the hybrid

Honda Civic.

In 1998 Toyota approached us and asked if we'd be interested in having their

Toyota Prius -- a new hybrid vehicle that had not yet been introduced into the

USA -- as our Pace car. To be honest, this offer presented a dilemma for

NESEA.

A gasoline vehicle, even an efficient gasoline vehicle, did not

demonstrate our dream of an EV charged by renewables. In fact, for several

years, we had allowed student hybrid vehicles (HEV) to enter, because the US

Department of Energy (DOE), which was a major sponsor of the Tour de Sol, also

sponsored a collegiate-level HEV competition, and they wanted to offer those

teams more opportunities to compete in events. We had reluctantly agreed,

since they held the purse strings, and again we reluctantly agreed to Toyota's

proposal for the same reason Pictured here is US DOE Secretary Pena waving the

checkered flag as the Toyota Prius arrived in DC. To be honest, this was also

an uncomfortable event for the DOE, because they did not want to recognize the

Prius because it was not ''made in the USA.'' In 1999 Honda became a major

sponsor of the Tour de Sol and shared the title sponsorship with the DOE for

the following three years. In 1999 Honda started showcasing the Honda Insight,

the first hybrid vehicle on the US market, and shortly thereafter the hybrid

Honda Civic.

At long last it became more politically acceptable to talk about climate change

-- and it became more widely accepted that it existed, and that we humans were

the primary cause.

At long last it became more politically acceptable to talk about climate change

-- and it became more widely accepted that it existed, and that we humans were

the primary cause.

As mentioned earlier, we added climate change emissions to our scoring system.

We also opened the event to all alternative fuel vehicles (AFV) --not just HEVs

using alternative fuels, but all vehicles that wanted to demonstrate how their

vehicles could meet the mission of the Tour de Sol -- which was more clearly

defined as ''reducing oil use and climate change emissions'' later to be know

as our goal of ''zero-zero.'' Needless to say, the opening of the doors was

hotly debated by the advisory committee, and it also resulted in a major

overhaul of the scoring system -- with the goal that we could demonstrate to

the world which path would lead to our ultimate goal of zero-zero. To avoid as

much controversy as possible, we used USDOE's Argonne National Laboratories

numbers generated by their GREET analysis. We understood that electricity and

alternative fuels could be made in many different ways, and that the climate

change emissions from these fuels varied depending on their feedstocks, and how

they were made. Therefore we knew there were warts in our scoring system, but

that they were no easily resolvable. Eventually, efficiency and climate change

emissions became more than 50% of the score. West Philadelphia High School was

one of the first teams to enter with an AFV.

Here they are receiving Honda's

Power of Dreams Award for their biodiesel Jeep.

As mentioned earlier, we added climate change emissions to our scoring system.

We also opened the event to all alternative fuel vehicles (AFV) --not just HEVs

using alternative fuels, but all vehicles that wanted to demonstrate how their

vehicles could meet the mission of the Tour de Sol -- which was more clearly

defined as ''reducing oil use and climate change emissions'' later to be know

as our goal of ''zero-zero.'' Needless to say, the opening of the doors was

hotly debated by the advisory committee, and it also resulted in a major

overhaul of the scoring system -- with the goal that we could demonstrate to

the world which path would lead to our ultimate goal of zero-zero. To avoid as

much controversy as possible, we used USDOE's Argonne National Laboratories

numbers generated by their GREET analysis. We understood that electricity and

alternative fuels could be made in many different ways, and that the climate

change emissions from these fuels varied depending on their feedstocks, and how

they were made. Therefore we knew there were warts in our scoring system, but

that they were no easily resolvable. Eventually, efficiency and climate change

emissions became more than 50% of the score. West Philadelphia High School was

one of the first teams to enter with an AFV.

Here they are receiving Honda's

Power of Dreams Award for their biodiesel Jeep.

When we opened the doors to all AFVs, a whole new flood of innovative vehicles

entered the event. On the left -- West Philadelphia High School build an eye-

catching kit car, the Attack that was fast and efficient and ran on biodiesel

On the right, University vehicles that had been modified to run on E85 (85%

ethanol and 15% gasoline) began to enter.

When we opened the doors to all AFVs, a whole new flood of innovative vehicles

entered the event. On the left -- West Philadelphia High School build an eye-

catching kit car, the Attack that was fast and efficient and ran on biodiesel

On the right, University vehicles that had been modified to run on E85 (85%

ethanol and 15% gasoline) began to enter.

The two vehicles that were most exciting to me were the two that really

demonstrated our idea of zero-zero. The upper left vehicle was built by

University of Wisconsin students. They converted a ''Sparrow,'' a briefly

produced one-person EV, to be a hybrid vehicle that ran on electricity and

hydrogen. When parked, they pulled out a PV panel and a small wind turbine to

recharge the batteries and make hydrogen for the next leg of the journey.

Western Washington University's Viking 32 is an amazing car that actually

reduces climate change emissions every mile that it drives! It is an efficient

purpose-built internal combustion engine vehicle that runs on methane (or

natural gas.) The methane came from the manure at a dairy farm near their

campus. Since methane is 20 times more effective as a global warming gas as

carbon dioxide, by burning methane and turning it into CO2, it is reducing

climate change emissions as it drives! While this idea is not cost effective

today, it could be in the near future -- and it is the kind of innovative and

long-term thinking that we need to really change the world!

The two vehicles that were most exciting to me were the two that really

demonstrated our idea of zero-zero. The upper left vehicle was built by

University of Wisconsin students. They converted a ''Sparrow,'' a briefly

produced one-person EV, to be a hybrid vehicle that ran on electricity and

hydrogen. When parked, they pulled out a PV panel and a small wind turbine to

recharge the batteries and make hydrogen for the next leg of the journey.

Western Washington University's Viking 32 is an amazing car that actually

reduces climate change emissions every mile that it drives! It is an efficient

purpose-built internal combustion engine vehicle that runs on methane (or

natural gas.) The methane came from the manure at a dairy farm near their

campus. Since methane is 20 times more effective as a global warming gas as

carbon dioxide, by burning methane and turning it into CO2, it is reducing

climate change emissions as it drives! While this idea is not cost effective

today, it could be in the near future -- and it is the kind of innovative and

long-term thinking that we need to really change the world!

In 2005, NESEA had to face the fact that the Tour de Sol had major economic

challenges. The Bush Administration was not interested in alternative fuels,

so we lost our DOE funding. Our funds from states started drying up as they

became strapped for cash. The auto companies had moved on from marketing

hybrid vehicles to ''early adopters'' that attended the Tour de Sol to

mainstream marketing. And schools were also struggling financially so it was

more difficult for student teams to build vehicles, and to come to an event

that was 8-days long! We therefore changed the event from an 8-day rally that

stopped in 5-12 communities to a 3-4-day ''hub and spoke'' event that had a

home base, with events that went out from that point. We also sought and found

a partner -- the Saratoga (NY) Automobile Museum -- who helped us reach

mainstream people interested in automobiles. Two new events were also born to

attract new entrants to the Tour de Sol. Josh Kerson Run, owner of Run About

Cycles, was interested in sharing information with other companies creating

electric bikes -- and so the Around Town Vehicle event was born. This event

not only attracted electric bike manufacturers, it also offered students an

opportunity to get involved with a project that was less expensive than a full-

size car. And it offered the Tour de Sol an opportunity to demonstrate low

impact non-auto travel options -- ''new fun ways of getting around!'' This

event grew to 15 entries within two years.

In 2005, NESEA had to face the fact that the Tour de Sol had major economic

challenges. The Bush Administration was not interested in alternative fuels,

so we lost our DOE funding. Our funds from states started drying up as they

became strapped for cash. The auto companies had moved on from marketing

hybrid vehicles to ''early adopters'' that attended the Tour de Sol to

mainstream marketing. And schools were also struggling financially so it was

more difficult for student teams to build vehicles, and to come to an event

that was 8-days long! We therefore changed the event from an 8-day rally that

stopped in 5-12 communities to a 3-4-day ''hub and spoke'' event that had a

home base, with events that went out from that point. We also sought and found

a partner -- the Saratoga (NY) Automobile Museum -- who helped us reach

mainstream people interested in automobiles. Two new events were also born to

attract new entrants to the Tour de Sol. Josh Kerson Run, owner of Run About

Cycles, was interested in sharing information with other companies creating

electric bikes -- and so the Around Town Vehicle event was born. This event

not only attracted electric bike manufacturers, it also offered students an

opportunity to get involved with a project that was less expensive than a full-

size car. And it offered the Tour de Sol an opportunity to demonstrate low

impact non-auto travel options -- ''new fun ways of getting around!'' This

event grew to 15 entries within two years.

Jim Dunn, CEO of the Center for Technology Commercialization was the instigator

of another new event -- the Monte Carlo-style Rally & 100-mpg Challenge. He

recruited Gilles Labelle, Craig Van Battenberg and others to create this

exiting event for hybrid and alternative fueled vehicle owners -- and

challenged them to demonstrate how efficiently they could drive their vehicles!

We were thrilled when the event attracted 50 entries the first year. It also

included several HEV owners that had modified their vehicles in various ways to

get even better performance -- with turbochargers, or extra battery packs.

Valence Technology brought the first plug-in hybrid (PHEV) to the event in

2005.

Jim Dunn, CEO of the Center for Technology Commercialization was the instigator

of another new event -- the Monte Carlo-style Rally & 100-mpg Challenge. He

recruited Gilles Labelle, Craig Van Battenberg and others to create this

exiting event for hybrid and alternative fueled vehicle owners -- and

challenged them to demonstrate how efficiently they could drive their vehicles!

We were thrilled when the event attracted 50 entries the first year. It also

included several HEV owners that had modified their vehicles in various ways to

get even better performance -- with turbochargers, or extra battery packs.

Valence Technology brought the first plug-in hybrid (PHEV) to the event in

2005.

In 2006, Hymotion, that offered a PHEV conversion kit for a Toyota Prius or

Ford Escape hybrid, showcased their vehicle -- although they did not compete

because our scoring system was not set up to showcase the advantages of such a

vehicle.

In 2006, Hymotion, that offered a PHEV conversion kit for a Toyota Prius or

Ford Escape hybrid, showcased their vehicle -- although they did not compete

because our scoring system was not set up to showcase the advantages of such a

vehicle.

So. Where do we go from here? The need has never been greater for changing how

we get around. The climate crisis, peak oil, war in the Middle East over oil,

the ever growing population and increased cars and demand for energy, and

environmental degradation due to our addiction to fossil fuels is growing all

issues that are looking for solutions.

So. Where do we go from here? The need has never been greater for changing how

we get around. The climate crisis, peak oil, war in the Middle East over oil,

the ever growing population and increased cars and demand for energy, and

environmental degradation due to our addiction to fossil fuels is growing all

issues that are looking for solutions.

When I look back on our successes I can see that: we have hybrids and biofuels

on the market; consumers are buying hybrids and asking for more fuel efficient

vehicles; and hundreds of young people have been involved in the event. Though

we are not in touch with most of them, we are hopeful that participating in the

Tour de Sol touched them in some way, and that whatever they are doing they are

carrying their understanding of the severity of the situation -- and are

working with us toward solutions

Others have also taken up our cause -- maybe not the cause of absolute zero-

zero, but the cause of incrementally working in that direction. Michelin Tire

Company created the Challenge Bibbendum in 2001 -- an international competition

that challenges the auto companies to demonstrate their vehicles on the market

today and prototypes that have good environmental performance.

http://www.challengebibendum.com/challenge/front/affich.jsp?&lang=EN

The Automotive X Prize was announced this year. It offers a multi-million dollar

prize to entrants that bring vehicles that get 100 mpg, meet EPA emissions

standards, and are fun to drive. Their goal is attract teams from around the

world ''to design viable, clean and super-efficient cars that people want to

buy.''

http://auto.xprize.org/

When I look back on our successes I can see that: we have hybrids and biofuels

on the market; consumers are buying hybrids and asking for more fuel efficient

vehicles; and hundreds of young people have been involved in the event. Though

we are not in touch with most of them, we are hopeful that participating in the

Tour de Sol touched them in some way, and that whatever they are doing they are

carrying their understanding of the severity of the situation -- and are

working with us toward solutions

Others have also taken up our cause -- maybe not the cause of absolute zero-

zero, but the cause of incrementally working in that direction. Michelin Tire

Company created the Challenge Bibbendum in 2001 -- an international competition

that challenges the auto companies to demonstrate their vehicles on the market

today and prototypes that have good environmental performance.

http://www.challengebibendum.com/challenge/front/affich.jsp?&lang=EN

The Automotive X Prize was announced this year. It offers a multi-million dollar

prize to entrants that bring vehicles that get 100 mpg, meet EPA emissions

standards, and are fun to drive. Their goal is attract teams from around the

world ''to design viable, clean and super-efficient cars that people want to

buy.''

http://auto.xprize.org/

But let's take a reality check Read the slide and you will get the sorry

picture of our lack of success in reducing oil use by increasing fuel

efficiency. What happened? People bought SUVs and auto makers made them.

Also the number of people and cars has increased over the past 18-years. If

you take action today and call your Congress people, we can change this by

raising the CAFE standards, and require auto makers to improve the fuel economy

of their vehicles. Alternative fuels can also be helpful, but I have always

been hesitant to embrace them with exuberance for several reasons. Firstly -

we have to focus on reducing the need first -- and put more fuel efficient

vehicles on the road, along with campaigns to walk, bike, take mass transit,

car pool, car share, and just drive less Secondly, we have to be ever vigilant

about ''unintended consequences.'' For example, already we have seen at least

two bad consequences of biofuels. The demand for corn to make ethanol has

driven up the cost of corn so people in Mexico cannot afford to buy tortias,

and New England farmers are going bankrupt because they cannot afford to feed

their dairy cows. The demand for oil to make biodiesel has already encouraged

people to cut down rain forests so they can plant palm oil trees and make

money. The net effect is more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Look at the

full cycle. Look at the feed stock. I have a huge fear that market trends

(like price of vegetable oil) will take this whole thing out of our hands and

spin the world out of control.

But let's take a reality check Read the slide and you will get the sorry

picture of our lack of success in reducing oil use by increasing fuel

efficiency. What happened? People bought SUVs and auto makers made them.

Also the number of people and cars has increased over the past 18-years. If

you take action today and call your Congress people, we can change this by

raising the CAFE standards, and require auto makers to improve the fuel economy

of their vehicles. Alternative fuels can also be helpful, but I have always

been hesitant to embrace them with exuberance for several reasons. Firstly -

we have to focus on reducing the need first -- and put more fuel efficient

vehicles on the road, along with campaigns to walk, bike, take mass transit,

car pool, car share, and just drive less Secondly, we have to be ever vigilant

about ''unintended consequences.'' For example, already we have seen at least

two bad consequences of biofuels. The demand for corn to make ethanol has

driven up the cost of corn so people in Mexico cannot afford to buy tortias,

and New England farmers are going bankrupt because they cannot afford to feed

their dairy cows. The demand for oil to make biodiesel has already encouraged

people to cut down rain forests so they can plant palm oil trees and make

money. The net effect is more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Look at the

full cycle. Look at the feed stock. I have a huge fear that market trends

(like price of vegetable oil) will take this whole thing out of our hands and

spin the world out of control.

If you read this slide you will see that we are on the cusp of beginning to

address and regulate climate change emissions. This is great news -- but it

will only happen if you take the initiative of call your Congress people and

telling them, and the EPA why they must act today on this issue.

If you read this slide you will see that we are on the cusp of beginning to

address and regulate climate change emissions. This is great news -- but it

will only happen if you take the initiative of call your Congress people and

telling them, and the EPA why they must act today on this issue.

What I see as the largest unmet need -- now that the Tour de Sol is no longer

running -- is a competition that would inspire young people -- and the 21st

Century Automotive Challenge has all the ingredients that offer this to high

school students! As noted in this slide, I'd prefer an event that had a wide

range of vehicles, like electric bikes and solar/electric off-road vehicles, in

the hope that if the event offered an opportunity to participate with less

expensive projects that more students would compete. But if there is not a

volunteer to take this on it would be best to let it go. It is clear to me

that the event, at least for now, has to be low cost. I do not see money from

the auto companies. The federal government will not have money until we have a

new administration. The state government might have some support, depending on

the state. For a low-cost event, volunteers become more important than ever.

They must now not only be on hand during the event, but volunteers must take on

planning, fundraising, registration, promotion etc. -- as the creators of the

21st Century Automotive Challenge have. Partnerships also become more

important -- as they enable an event to not only cut costs (no site rental

fees) but also to reach a larger audience than the event organizers could reach

on their own. (examples are the Saratoga Automobile Museum, Burlington County

Earth Fair.)

What I see as the largest unmet need -- now that the Tour de Sol is no longer

running -- is a competition that would inspire young people -- and the 21st

Century Automotive Challenge has all the ingredients that offer this to high

school students! As noted in this slide, I'd prefer an event that had a wide

range of vehicles, like electric bikes and solar/electric off-road vehicles, in

the hope that if the event offered an opportunity to participate with less

expensive projects that more students would compete. But if there is not a

volunteer to take this on it would be best to let it go. It is clear to me

that the event, at least for now, has to be low cost. I do not see money from

the auto companies. The federal government will not have money until we have a

new administration. The state government might have some support, depending on

the state. For a low-cost event, volunteers become more important than ever.

They must now not only be on hand during the event, but volunteers must take on

planning, fundraising, registration, promotion etc. -- as the creators of the

21st Century Automotive Challenge have. Partnerships also become more

important -- as they enable an event to not only cut costs (no site rental

fees) but also to reach a larger audience than the event organizers could reach

on their own. (examples are the Saratoga Automobile Museum, Burlington County

Earth Fair.)

The Tour de Sol could never have existed without its volunteers. Volunteers

have shaped the mission of the event, the Rules and the scoring system.

Volunteers do the tech testing, the scoring, the recharging and refueling, the

site decoration, the photography, the public education and much more.

Volunteers worked in each community before the event to create a unique event

that would be exciting and attractive for their community. Volunteers have

created new Tour de Sol events. As you can see, the volunteers are the heart

and soul of the Tour de Sol.

The Tour de Sol could never have existed without its volunteers. Volunteers

have shaped the mission of the event, the Rules and the scoring system.

Volunteers do the tech testing, the scoring, the recharging and refueling, the

site decoration, the photography, the public education and much more.

Volunteers worked in each community before the event to create a unique event

that would be exciting and attractive for their community. Volunteers have

created new Tour de Sol events. As you can see, the volunteers are the heart

and soul of the Tour de Sol.

Young people are the future. In addition to the many entries from high

schools, colleges, and universities, NESEA developed curricular materials for

middle and high school students -- everything from a 150 page resource for high

school teachers, to trip tally exercises for elementary school students, the

Junior Solar Sprint for middle school students, and scavenger hunts and more

for classes that wanted to take a field trip to the Tour de Sol. These

classroom resources are downloadable free from the NESEA web site at

www.NESEA.org

Click on the K-12 education section.

Young people are the future. In addition to the many entries from high

schools, colleges, and universities, NESEA developed curricular materials for

middle and high school students -- everything from a 150 page resource for high

school teachers, to trip tally exercises for elementary school students, the

Junior Solar Sprint for middle school students, and scavenger hunts and more

for classes that wanted to take a field trip to the Tour de Sol. These

classroom resources are downloadable free from the NESEA web site at

www.NESEA.org

Click on the K-12 education section.

I want to put the Tour de Sol in context of an overall plan to reduce climate

change emissions. NRDC (The Natural Resources Defense Council) has a plan to

reduce carbon emissions by 60% over the next 50 years. This graph shows how we

can lower carbon emissions from the base case of ''doing nothing.'' The slope

at the top represents ''doing nothing'' i.e. ''business as usual' (BAU) The

first ''wedge'' shows how using energy efficient lights and appliances etc. can

reduce our electrical demand and therefore our carbon emissions. The second

wedge shows how making our buildings more energy efficient can reduce overall

energy use (by reducing the need for oil, gas, and electricity) The third wedge

is ''our wedge.'' I'll talk more about this in the next slide The fourth wedge

shows how we can reduce carbon emissions by improving the efficiency of our

large trucks and air planes, and by encouraging people to drive less by

implementing smart growth strategies, and making it easier for people to walk,

bike, use mass transit, car pool, or car share. The fifth wedge is using

renewable technologies to produce zero-carbon energy. The final and sixth

wedge is the carbon emission reductions that could be achieved if carbon

sequestration technologies were developed. This technology would capture the

carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants and then bury that carbon

underground.

I want to put the Tour de Sol in context of an overall plan to reduce climate

change emissions. NRDC (The Natural Resources Defense Council) has a plan to

reduce carbon emissions by 60% over the next 50 years. This graph shows how we

can lower carbon emissions from the base case of ''doing nothing.'' The slope

at the top represents ''doing nothing'' i.e. ''business as usual' (BAU) The

first ''wedge'' shows how using energy efficient lights and appliances etc. can

reduce our electrical demand and therefore our carbon emissions. The second

wedge shows how making our buildings more energy efficient can reduce overall

energy use (by reducing the need for oil, gas, and electricity) The third wedge

is ''our wedge.'' I'll talk more about this in the next slide The fourth wedge

shows how we can reduce carbon emissions by improving the efficiency of our

large trucks and air planes, and by encouraging people to drive less by

implementing smart growth strategies, and making it easier for people to walk,

bike, use mass transit, car pool, or car share. The fifth wedge is using

renewable technologies to produce zero-carbon energy. The final and sixth

wedge is the carbon emission reductions that could be achieved if carbon

sequestration technologies were developed. This technology would capture the

carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants and then bury that carbon

underground.

This graph shows in more detail the challenges that all of the Tour de Sol

entrants are working on. It shows how NRDC thinks we are going to reduce

carbon emissions from business as usual (BAU) from the transportation sector.

The most amazing thing to me is their prediction that we can cut carbon

emissions from passenger vehicles by 85%! You can see on the right that a

majority (64%) of the overall gains are from vehicle efficiency. 29% is from

switching to less carbon intensive fuels (electricity, natural gas, and

biofuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, and methane instead of gasoline and

diesel.) And 7% is from smart growth -- getting people to drive less. Since

today in the US, 2/3rds of all the oil is used for transportation, and one

third of all the greenhouse gas emissions are emitted from transportation, the

work that everyone is doing through the Tour de Sol is critically important.

This graph shows in more detail the challenges that all of the Tour de Sol

entrants are working on. It shows how NRDC thinks we are going to reduce

carbon emissions from business as usual (BAU) from the transportation sector.

The most amazing thing to me is their prediction that we can cut carbon

emissions from passenger vehicles by 85%! You can see on the right that a

majority (64%) of the overall gains are from vehicle efficiency. 29% is from

switching to less carbon intensive fuels (electricity, natural gas, and

biofuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, and methane instead of gasoline and

diesel.) And 7% is from smart growth -- getting people to drive less. Since

today in the US, 2/3rds of all the oil is used for transportation, and one

third of all the greenhouse gas emissions are emitted from transportation, the

work that everyone is doing through the Tour de Sol is critically important.

In closing, I would like to thank everyone that has helped with the Tour de Sol

over the many years that I have been associated with it. Please see slide for

this list. I would also like to thank those that are carrying the ball

forward. Ollie Perry, Paul Kydd, past Tour de Sol volunteers, and many others

that I know were working behind the scenes in birthing the 21st Century

Automotive Challenge.

In closing, I would like to thank everyone that has helped with the Tour de Sol

over the many years that I have been associated with it. Please see slide for

this list. I would also like to thank those that are carrying the ball

forward. Ollie Perry, Paul Kydd, past Tour de Sol volunteers, and many others

that I know were working behind the scenes in birthing the 21st Century

Automotive Challenge.

In closing I'd like to show you a photograph taken in 1989 -- at the start of

the Tour de Sol. The young boy in the foreground is Rob's son Tyler -- who is

now a college student. I'd also like to share with you an oft-cited quote from

Margaret Mead, renowned sociologist. ''A small group of thoughtful people

could change the world.

Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.''

I challenge everyone reading this to pick up the torch and run with it.

The future is in your hands.

In closing I'd like to show you a photograph taken in 1989 -- at the start of

the Tour de Sol. The young boy in the foreground is Rob's son Tyler -- who is

now a college student. I'd also like to share with you an oft-cited quote from

Margaret Mead, renowned sociologist. ''A small group of thoughtful people

could change the world.

Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.''

I challenge everyone reading this to pick up the torch and run with it.

The future is in your hands.